The Beginnings of the Alphabet, Exert Edward Clodd Exposition

The Beginnings of the ALPHABET

The Beginnings of the ALPHABET

From :The Story of the Alphabet”

The beginnings of the Alphabet is an exert from the Project Gutenberg EBook of The Story of the Alphabet, by Edward Clodd. This material is for application and distribution by anyone anywhere at no cost and with relatively no restrictions. Copy it. Share it. Give it away. Or re-use according to Public Domain licensing and the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org

Title: The Story of the Alphabet Author: Edward Clodd Release Date: July 24, 2014 [EBook #46388] Language: English Character set encoding: UTF-8

The associated ebook file. “The Story of the Alphabet,” produced by Chris Curnow, Paul Marshall and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from images generously made available

by The Internet Archive). Images used in this exert taken from the original content. View full Project Gutenberg License here.

Alphabet, The Beginnings

We may, without further preface, advance to our main purpose, which is to supply an account of the stages through which the alphabets of the civilized world passed before they reached their, practically, final form. Here, as in aught else that the wit of man has devised and the cunning of his hand applied, the law of development is seen at work. In the quest for traces of any fundamental differences between him and the animals to which he stands in nearest physical and psychical relation, he has been variously described as tool-maker, fire-maker, possessor of articulate speech, and so forth; but the further that observation and comparison have been made, the more apparent has it become that those differences are of degree and not of kind. Some evidence in support of this has been already summarized in previous volumes of this series; and here it suffices to say that it is in the inventive arts, as e.g. the production of fire, of the mode of which nature supplied the hints, and the making of pictorial signs, in which the mimetic instinct, shared by some of the lower animals, comes into play, [Pg 24] that, restricting the comparison to things material, man appears upon a higher plane. But this has been reached by processes of development involving no break in the continuity of things.

In this “story” we start with man as sign-maker. His prehistoric remains supply evidence of artistic capacity in a remote past, and set before us in vigorous, rapid outline what his life and surroundings must have been. On fragments of bone, horn, schist, and other materials, the savage hunter of the Reindeer Period, using a pointed flint flake, depicted alike himself and the wild animals which he pursued. From cavern-floors of France, Belgium, and other parts of Western Europe, whose deposits date from the old Stone Age, there have been unearthed rude etchings of naked, hardy men brandishing spears at wild horses, or creeping along the ground to hurl their weapons at the urus, or wild ox, or at the woolly-haired elephant. A portrait of this last named, showing the creature’s shaggy ears, long hair, and upwardly curved tusks, its feet being hidden in the surrounding high grass, is one of the most famous examples of Paleolithic art.

Here let us pause to say that the apparent absence of other indications of man’s presence, showing passage from lower to higher stages of culture, led to the assumption that vast gaps have occurred in his occupancy of north-western and other parts of Europe. The theory of absolute disconnection between the Old Stone Age and the Newer Stone Age long held the field, but it has disappeared before the evidence [Pg 25] against tenantless intervals of areas in prehistoric times. And so with succeeding periods. There is no warrant for assuming entire effacement of one race, with resulting clear field for the immigration of another race; and modern archeological research is producing the links which connect the rude art of Northern with that of Southern  Europe, and, what will be shown to be of great moment, with that of the Eastern Mediterranean.

Europe, and, what will be shown to be of great moment, with that of the Eastern Mediterranean.

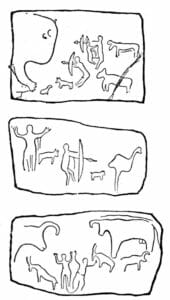

The examples of this must remain rare, since only pictographs on some durable material, or specimens of the fictile art, would survive the action of time. But, happily, if they are infrequent, they are widely distributed. For to those yielded by the bone-caverns already referred to are to be added rock-carvings in Denmark, and figures on limestone cliffs of the Maritime Alps; there are curious graphic signs, suggestive to some eyes of a primitive script, in the Marz d’Azil cave; while still more interesting are the animal and fylfot or swastika-like figures (the swastika is a solar symbol) “painted probably by early Slavonic hands on the face of a rock overhanging a sacred grotto in a fiord of the Bocche di Cattaro.” To this last-named example, given by Mr. Arthur Evans in his paper on “Primitive Pictographs” (Journal of Hellenic Studies, xiv. ii. 1894) may be added some pregnant remarks by the same authority. “When we recall the spontaneous artistic qualities of the ancient race which has left its records in the carvings on bone and ivory in the caves of the ‘Reindeer Period,’ this evidence of at least partial continuity on [Pg 26] the northern shores of the Mediterranean suggests speculations of the deepest interest. Overlaid with new elements, swamped in the dull, though materially higher, Neolithic civilization, may not the old æsthetic faculties which made Europe the earliest-known home of anything that can be called human art, as opposed to mere tools and mechanical contrivances, have finally emancipated themselves once more in the Southern regions, where the old stock most survived?

In the extraordinary manifestations of artistic genius to which, at widely remote periods and under the most diverse political conditions, the later populations of Greece and Italy have given birth, may we not be allowed to trace the re-emergence, as it were, after long underground meanderings, of streams whose upper waters had seen the daylight of that earlier world?” (Presidential Address to the Anthropological Section, British Association. Nature, 1st Oct. 1896.)

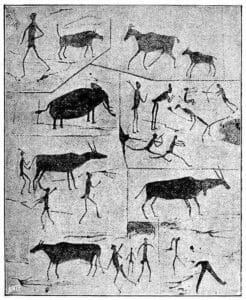

But man at the same stage of culture being everywhere practically the same, there is, in the paucity of examples from the Europe of the past, compensation in the specimens of graphic art found among extant barbaric folk. It is probable that a good proportion of these lack significance, but the pictograph is the parent of the alphabet, and therefore the careful transcripts of rock and other paintings which explorers have made may yet prove to be of value when interpreted in the light of examples whose gradations have been traced. Since the extinction of the Tasmanians, whom anthropologists regard as the nearest approach to Palæolithic man, the Australians stand, in certain respects, at the bottom of the scale, although the ingenuity of their social organizations warrants hesitation in making them the nadir of human kind. But as the reproductions show (Figs. 3 and 3a), their attempts at art are inferior to the spirited designs of the prehistoric cave-dwellers.

Read full Story of the Alphabet.

Bibliographic Record

| Author | Clodd, Edward, 1840-1930 |

|---|---|

| LoC No. | 95200462 |

| Title | The Story of the Alphabet |

| Language | English |

| LoC Class | P: Language and Literature |

| Subject | Alphabet |

| Subject | Writing — History |

| Category | Text |

| EBook-No. | 46388 |

| Release Date | Jul 24, 2014 |

| Copyright Status | Public domain in the USA. |

| Downloads | 38 downloads in the last 30 days. |

| Price | $0.00 |

Going Beyond the Alphabet, Recommended Reading

11 Secrets of Getting Published